This week I must report both sad news, and happy news. I debated making two posts of this and keeping them separate, yet the two subjects collide in an odd manner, due to a shared theme: Death.

I have spent a great deal of my life contemplating death. I have, on several occasions, attempted to end my own life. The last occasion, in the summer of 2011, was so very nearly successful that I have found people have acted differently around me since. Friends, family, it’s like they caught a glimpse of something horrific, something so utterly terrifying that they are almost afraid to look at me in case they see it again.

I did not truly understand this reaction. I understood, in the abstract, the notion that people hate the thought of someone they love taking their own life, because it means they will have to mourn the loss. They will have to grieve. And that will be unpleasant for them. I have often heard it said that the act of suicide is one of the most selfish things a person can do, and I have been told—by more than one friend or relative—that I ‘have’ to keep living because it would be unfair of me to die. It would be selfish of me to inflict the pain of losing me on people for whom I profess I care.

I have never seen it this way, and have in fact always viewed it from the alternate perspective: I have always found it utterly selfish of my friends and family to expect me to live through times in my life when I have wanted nothing more than to die. Since my diagnosis and the start of proper treatment and medication, as my life has so painfully slowly started to get back on track and I have begun, ever so cautiously, to hope that the worst is behind me, I find myself wishing less and less that I were dead. As I’m sure you can understand, everyone I know seems pleased by this, but I still find it incredibly hard to articulate to anyone ‘in the throws’, as it were, of an episode, exactly why it is a bad idea to try and kill themselves.

I have never seen it this way, and have in fact always viewed it from the alternate perspective: I have always found it utterly selfish of my friends and family to expect me to live through times in my life when I have wanted nothing more than to die. Since my diagnosis and the start of proper treatment and medication, as my life has so painfully slowly started to get back on track and I have begun, ever so cautiously, to hope that the worst is behind me, I find myself wishing less and less that I were dead. As I’m sure you can understand, everyone I know seems pleased by this, but I still find it incredibly hard to articulate to anyone ‘in the throws’, as it were, of an episode, exactly why it is a bad idea to try and kill themselves.

After all, it’s rather hypocritical, is it not, for me to sit there and say ‘no matter how bad it gets, you should never resort to that, it’s not an answer’, for I myself HAVE resorted to that, because at the time it felt very much like it WAS the only answer. When I was feeling like that I despised those people around me who told me I couldn’t do the one thing I was absolutely convinced would end my suffering. As a result, I feel useless when confronted by a person in that state of mind, because I know full well there is not one single thing—and I really do mean NOT. ONE. SINGLE. THING—that can be said to make them feel better, and anything you do say is likely to make it worse.

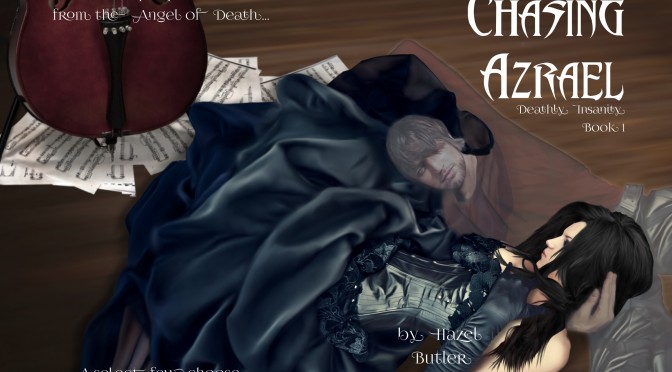

To that end—and here we come to my good news—I began writing a series of books exploring notions such as these, in an effort to provide something tangible to those people who felt like I had, both in the past and often during the time I was writing the first one.

Chasing Azrael is a novel about Death. More specifically, it is a novel about the obsession with Death, and how it can lead people to take their own lives, or spend so much of their time fixating on taking their own lives that they have no real life to speak of anyway. I began this novel in 2010, when I was first diagnosed with rapid cycling, Bipolar Disorder I. For the first time in my life I had a reason for some of the things that had happened to me, the way I had felt at certain times, and the possibility that it might get better. I was, to my horror, to find that it had to get considerably worse before things ultimately began to improve, but as I wrote my book, and tackled issues of plot, and dialogue, and characterisation, I found it was something I could hold onto in times when I was feeling impossibly low.

I designed the novel very carefully. It is not a manual for suicide, but rather a warning for those who contemplate it, and for the people in their lives who may—albeit unwittingly—be pushing them towards it through sheer ignorance. For years I had lived with friends and family who could not understand my often utterly irrational behaviour. My relationships with most of my family were strained, and the friends I had one by one fell away, until I was, at one stage, left with absolutely nobody but my brother, to whom I am eternally grateful for always standing by me, giving me a place to stay and a job. When I was diagnosed this changed. People became more understanding. Some of the friends who had abandoned me came back, realising that whatever it was I had done to upset them I had not intended, I had not meant, and more often than not I had not had the slightest amount of control over. The same was true of my family. My mother and sister are now a huge part of my life, something that was simply never the case before, as neither of them could understand me, and I resented them for it. My brother, on the other hand, went the other way. We have grown apart since, partly due to him getting a girlfriend, settling down, and us seeing less and less of each other, but partly also because the mention of my condition unnerves him. It makes him… uncomfortable. You can see it in his face whenever it comes up in conversation. I do not think he is consciously aware of it, but for whatever reason, he won’t talk about it. Almost as if, if he can pretend it’s not there, somehow it will go away and stop bothering his little sister.

I designed the novel very carefully. It is not a manual for suicide, but rather a warning for those who contemplate it, and for the people in their lives who may—albeit unwittingly—be pushing them towards it through sheer ignorance. For years I had lived with friends and family who could not understand my often utterly irrational behaviour. My relationships with most of my family were strained, and the friends I had one by one fell away, until I was, at one stage, left with absolutely nobody but my brother, to whom I am eternally grateful for always standing by me, giving me a place to stay and a job. When I was diagnosed this changed. People became more understanding. Some of the friends who had abandoned me came back, realising that whatever it was I had done to upset them I had not intended, I had not meant, and more often than not I had not had the slightest amount of control over. The same was true of my family. My mother and sister are now a huge part of my life, something that was simply never the case before, as neither of them could understand me, and I resented them for it. My brother, on the other hand, went the other way. We have grown apart since, partly due to him getting a girlfriend, settling down, and us seeing less and less of each other, but partly also because the mention of my condition unnerves him. It makes him… uncomfortable. You can see it in his face whenever it comes up in conversation. I do not think he is consciously aware of it, but for whatever reason, he won’t talk about it. Almost as if, if he can pretend it’s not there, somehow it will go away and stop bothering his little sister.

This reaction is understandable, but it is not helpful. To a person who has a condition like bipolar, it is necessary for the people in their lives to be as understanding as they can manage to be, to have as much comprehension of their condition as they can, if for no other reason than to keep them from saying things like ‘well, we’re all down sometimes’, when you’ve phoned them from the railings of a very high bridge and are on the verge of jumping. The people in your life need to know what they can and can’t say when you are in the various states that overtake you. They need to know how best to handle you, and when they are really best not handling you at all. Perhaps most importantly though, they need to acknowledge that you have a mental health illness, that this is not your fault, that it doesn’t make you ‘wrong’ in the head, or any less of human being, and that it is no different, not really, to any number of physical condition such as diabetes. One involves changing levels of insulin over which you have no control, the other involves changing brain chemicals over which you are similarly powerless.

To that end, I also wanted my books to provide people who didn’t have any kind of mental health problems with a deeper understanding of what it is like to live with such conditions. It’s a tall order, but I would like nothing more than for someone with no history of depression to pick up my book, read it, and come away not only having (hopefully) enjoyed a good story, but also with the feeling that they know, at least a little, what it is like to live with being depressed, to such an extent that you regularly consider ending your own life, and that to you, that is not an abhorrent or selfish act to contemplate, it is the light at the end of a tunnel full of horrors, the glimmer of hope in an otherwise desolate landscape. I want them to come away understanding why to people like me, it isn’t the ones who commits suicide who appears selfish, but the ones who repeatedly keep a person from dying. In short, I want to pick my readers up, take them to the very brink of insanity, then yank them back to the world of the living, a place where yes, they can acknowledge how bad it gets, yes, they can understand the impulse to do it, the need to have it over, but they can also see that there is a way back from that place.

I want the people who have stood on that bridge to know there is a way down.

And I want the people who have been on the other end of the phone while they were up there to know that once they are down, they can find a way to have a life again.

It’s a long time since I have actively contemplated killing myself. I had a slightly dicey few weeks around October-December last year when I recognised how I was feeling and I knew it was possible I’d get that impulse again. I handed my MEDs over to my mother who has had them under lock and key ever since.

It’s a long time since I have actively contemplated killing myself. I had a slightly dicey few weeks around October-December last year when I recognised how I was feeling and I knew it was possible I’d get that impulse again. I handed my MEDs over to my mother who has had them under lock and key ever since.

You are probably wondering how on earth I can possibly class this as ‘happy’ news, and if this is the good, what the hell is the sad?

Well, the happy news is that Chasing Azrael is soon to be released on the world. As of the 26th of April it will be available in paperback and Kindle formats, from Amazon and a host of other retailers, as well as directly from myself. For those of you who read this blog regularly and enjoy my writing, I hope that you will pick up a copy, but more than that, I hope that you will let me know what you think of it. I am still writing the remaining books in the series, and I want to ensure the rest—one in particular, which is very personal to me—really achieve the effect I have in mind.

And this of course leads me to the sad news. I have begun to understand over the last week or so why it is my friends and family have had that look about them since my last suicide attempt so very nearly worked. On the 5th of January I lost a very dear friend. To say that her death was unexpected would be redefining the word to mean something infinitely stronger than its current denotation. She was young; she was healthy; she has three teenage children. I was speaking to her on January 1st. We were thanking each other for our respective Christmas cards and talking about AuthorCon, a convention of independently published authors which is taking place in Manchester, on April 26th, and at which I will be launching my book. Lindsey, also a writer, had booked a table and was planning to come up, along with another friend of ours (again, another writer, you can see a trend here…), so that it would be the three of us signing books at the convention. I was incredibly excited about this, not only because it was my book launch but because it meant meeting Lindsey in the flesh. The latter was pleasing because despite her being a very good friend, we never actually met. We knew each other only via an online writing group of which we are both members.

She went out for a walk with her family later that day, came home, began complaining of back pains, and was rushed to hospital. Despite an operation that appeared to be successful, she was placed in a medically induced coma. She never woke up. I cannot adequately describe the utter shock, and horror, that I felt when I was told. I have lost people before, but only elderly relatives, people who had been ill for prolonged periods of time and whose death was, while still terribly painful, not unexpected and in some ways a relief, as you knew it was inevitable, and hated seeing them in that amount of pain.

Now I know what horror it was my friends and family glimpsed, that last time I tried to die.

Now I understand why people say it’s selfish.

It’s not because they enjoy seeing you in pain, not because they think it’s better that you suffer than they do, it’s the sheer fallout of it. The impact one death has is as a fall of a well-placed domino; one goes down, the rest soon follow. I do not know Lindsey’s family, although they have been in my thoughts a lot these past days. I do however know a lot of her online friends, many of whom were in our writing group, and many of whom are currently feeling as lost and broken as I am over the whole thing. The shock is bad enough. The loss when you have actually managed to process it is unbearable.

It’s not because they enjoy seeing you in pain, not because they think it’s better that you suffer than they do, it’s the sheer fallout of it. The impact one death has is as a fall of a well-placed domino; one goes down, the rest soon follow. I do not know Lindsey’s family, although they have been in my thoughts a lot these past days. I do however know a lot of her online friends, many of whom were in our writing group, and many of whom are currently feeling as lost and broken as I am over the whole thing. The shock is bad enough. The loss when you have actually managed to process it is unbearable.

The issue that I have here is that I only ever knew Lindsey online. I found myself sending her an invitation via Facebook yesterday, because for a few moments I forgot. It was second nature to me, to include her in the things I do. I hit the invite button and immediately felt a fresh wave of grief, as if being told for the first time all over again. There is an oddness to the internet. Her profile is still there, so in many respects she has the appearance of still being there, as much as she ever was previously. It takes a minute to recall that she is no longer on the other end of this infinite thing we call ‘Internet’.

And that thought got me wondering. If my entire friendship with Lindsey can take place across the vast void of cyberspace, can it not somehow continue across the void that now exists between this world, the ‘living’ worlds, and wherever it is she has gone?

I am not a religious person, but I have spent a considerable amount of time thinking about what happens to a person after they die. Chasing Azrael can be described in many ways. It’s urban fantasy; a supernatural mystery; gothic literature, but at the heart it is one very simple thing: it’s a ghost story.

Throughout the book I explore why people die, as well as what happens to them afterwards. I have often wondered what, had I been successful in any of my attempts, would have happened to me after. Would I truly have felt any better? Would the bipolar be gone once I no longer had a physical brain with that pesky chemical imbalance? If I no longer had bipolar, would my personality alter drastically, or would I still possess all the same flaws I currently have, because the bipolar did not cause them, but merely amplified them, the repeated trauma experienced as a result of my mood swings affecting the person I was to the point that, even if you took the bipolar away, and I no longer had that awful pendulum in my head, I would still be as I had become as a result of my experiences. It’s easy to blame it all on the bipolar, but one must also take responsibility for one’s own actions, one’s own faults, and acknowledge that while you may not have developed them were it not for the bipolar, once you have them, and are aware of them, it is your responsibly to control them wherever possible.

This week I have found myself thinking about Lindsey, and whether or not she is ‘out there’ somewhere, in a world such as the ghostly world I have imagined for my novels. I wonder if she can see how much she is missed, and how much she is loved, and I wonder if that would make it easier or harder for her. I am still working on the final edits of the novel, and I have to say that having so recently suffered the loss of a friend I find myself looking at it with new eyes.

Lindsey was a great writer, a wonderful friend, and a great help to me at a time when I was very much alone and my life was a complete mess. She read several drafts of my novel, offering comments and help on each, and was supposed to be present on the day it was launched. I will miss her terribly, and although I look forward to the release of my novel, I know the day will be tinged with grief no matter my excitement, because someone who should have been there, won’t be.

Or will she?

I realises this has been a much longer post than usual, and I thank those of you who have taken the time to read to the end. I would also like to leave you with a final thought for consideration:

Death can only be an answer if you fully understand the question, and it is difficult to understand anything fully when you are in the midst of a depressive episode.

Moreover, death may not be the end you think it is, and if it isn’t, if you wake in some new world to find you’re just as broken in that one as you were in this one, what will you do then?

There will be nothing to do but stare down at the ones you left behind, and watch them all fall after you.