Few novels have proven to be as disappointing as this one.

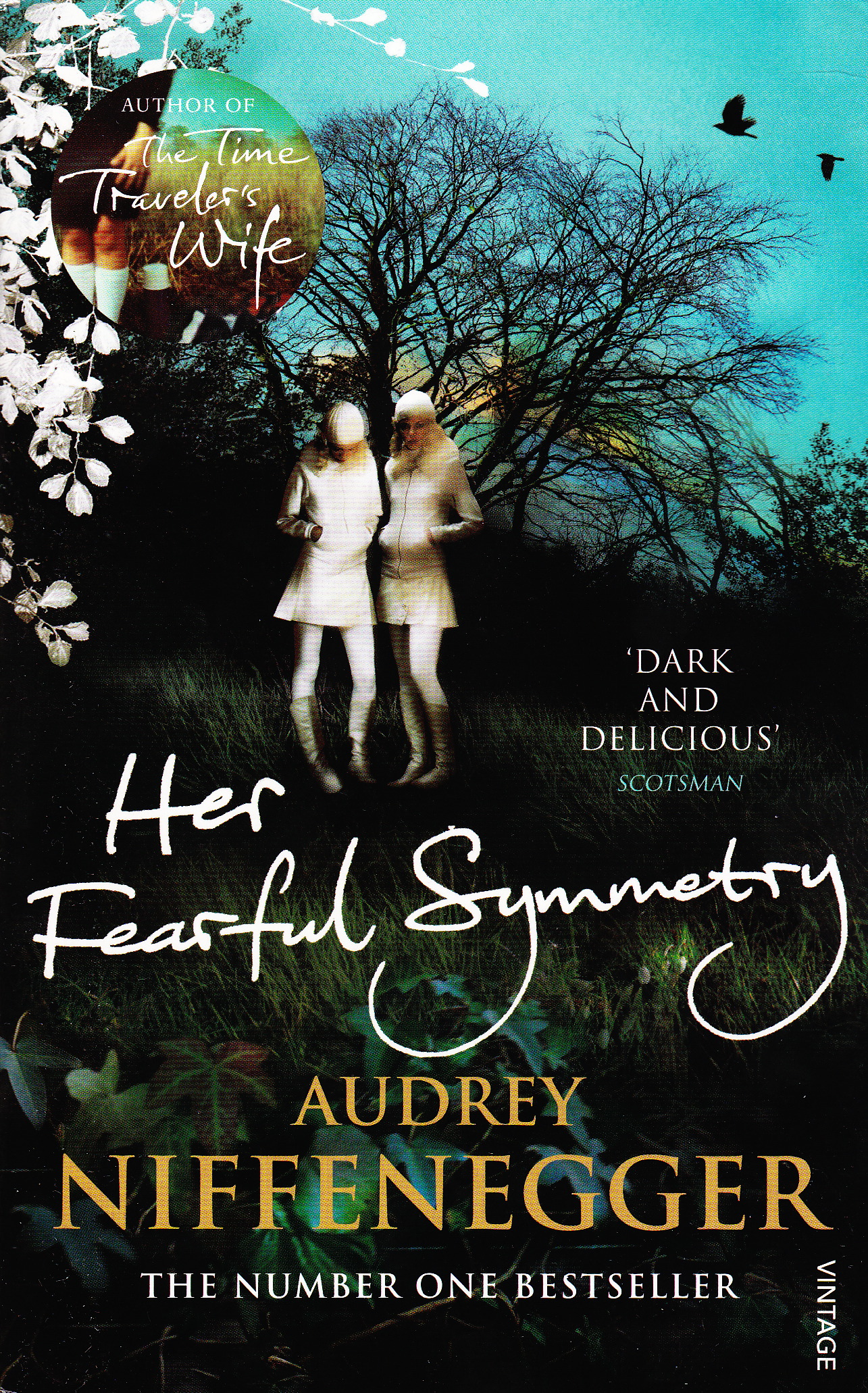

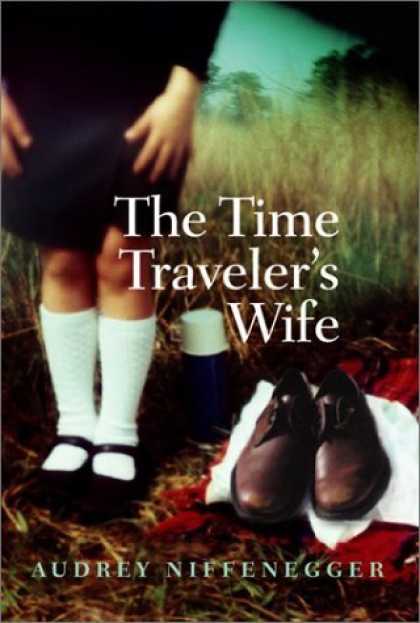

The Time Traveller’s Wife was a wonderful read; not perfect, but still very enjoyable, beautifully written, and with a very unique premise. Her Fearful Symmetry held the expectation of more. The title alone is evocative. William Blake wrote The Tyger about light, and dark, and how one cannot be without the other: good cannot exist without evil. The ‘fearful symmetry’ is a reference to this, while the central characters of the novel – Julia and Valentina – are ‘mirror twins’. Add to this the setting in the shadow of High Gate Cemetery and the possibilities were astonishing. The woman who wrote The Time Traveller’s Wife must surely do wonders with this concept.

Or not.

Billed as ‘a delicious and deadly ghost story about love, loss and identity’, Her Fearful Symmetry fails on every single count bar one – it involves a ghost. The central ‘romance’ in the novel is between Robert and Elspeth, who dies in the first line of the book, and it is her ghost who provides the majority of the rather ill-conceived plot. Robert grieves, as anyone would, however his grief is hindered by the revelation that Elspeth’s ghost is still present. He then forms a tentative relationship with one of the twins – Valentina, or ‘Mouse’ as her sister Julia calls her – although this is more due to her resemblance to Elspeth than anything else.

There is little true love in this book. The most resounding ‘love story’ in fact revolves around two minor characters living in the house next to the cemetery. Martin and Marijke are hopelessly in love, however Martin has some serious mental health issues, which have proven impossible for Marijke to live with any longer. She leaves him, not because she no longer loves him, but because she loves him enough to understand her absence is the only thing which might convince him to help himself, and get better. She issues an ultimatum: she will take him back, if he is able to leave the house, and follow her to Amsterdam. This element of the plot is genuinely interesting, and when Julia becomes friends with Martin, takes on an entirely different aspect which could have been truly spectacular. It is actually Julia’s attempts to help Martin, and her love for Valentina, which are the most touching elements of the story, while Julia’s pain over events ultimately prove to be the truest emotions in the whole novel.

The notion of identity is never explored in any depth. There is a poorly constructed plot line concerning Julia and Valentina, in which Julia is supposedly the dominant and bossy twin, and Valentina follows her lead, does as she’s told, and fiercely resents Julia for it. The old adage of ‘show don’t tell’ applies here, for while we are told a few times that Valentina feels smothered by her sister and desperate to get away from her, we never truly feel that is the case. While we can sympathise with the ‘Mouse’, she has ample opportunity to assert her independence and never takes advantage. Her attempts to display her own identity, and fight Julia, are limited and badly written, the result of which being that later plot developments, which hinge on Valentina’s supposed desire for independence, simply do not work; the reader never feels Valentina’s desperation, and so her extreme actions are unbelievable, since they lack motivation.

The other aspect to the plot concerning identity is the fully predictable, badly plotted, and confusingly explained history between Elspeth and her own twin sister, Edwina, mother of Julia and Valentina. The intention here is clear: Elspeth and Edwina, themselves twins, had their own issues when it came to finding their identities. This is then ‘mirrored’ in the ‘mirror twins’, who are supposed to be struggling with identity issues of their own . Again, had it been handled correctly and well written, it could have been an excellent subplot. As it stands, the explanation of it is so convoluted – despite what happened being obvious from the first chapter – that it borders on ridiculous. There is no logic behind the actions of any of the characters involved. They behave irrationally, believing the unbelievable, accepting the unacceptable, and spending lifetimes doing things without motivation. It is a poorly designed plot mechanism intended to draw the reader through the first three quarters of a very uneventful novel with the promise of a ‘big secret’ which, as it turn out, is neither big nor in any way a secret, either to the characters involved or the reader.

Elspeth’s ghost is another wasted element, doing nothing of interest until the very end of the book. In fact, everything of interest happens at the very end of the book, yet the ending is not only rushed, but redundant.

This novel has often been described as ‘Gothic’, yet there is nothing Gothic about it until one scene at the very end which is truly macabre; had the rest of the narrative had this feel to it, the novel would have been spectacular. There are a few random references thrown in as an attempt to create a ‘Gothic’ feel: the twins discuss Steampunk in two lines of dialogue, overheard by another character who doesn’t understand what they’re talking about; Valentina tries and fails to make a black velvet ‘Goth’ dress for herself; and one of the twins remark that Robert would be a ‘Goth’ if he were a teenager.

This does not a Gothic novel make.

There are only three truly Gothic aspects of this novel and all are totally wasted. The ghostly elements could have been turned into so much more. There is a beautiful scene early on, of children playing in the graveyard, and it is obvious even at that point that these children are ghosts. Yet they are not mentioned again until the very end. While Niffeneger clearly did her research on Highgate Cemetery, it is delivered in sections that feel more like lectures than quality fiction. The setting should have created an atmosphere, a feel of the dark, ghostly and ethereal elements the author clearly wanted to portray, yet it does not. It is clinical. Further to this, the Gothic genre is not just about cemeteries and ghosts; it’s about horror, and human nature, the gender roles that underpin society, and the evils that men (and women) do. Only one aspect of the whole novel achieves this, and it is dropped into the plot near the end, executed swiftly, and then rushed so much you could literally miss it.

The ‘twist’ at the end is poorly executed, unfounded, and ultimately unbelievable. Ironically it is not the fantastic elements of the plot that make it unconvincing, but the fact that the previous actions and responses of the characters do not substantiate such a turn of events; you simply cannot believe any of those involved in the final sequence would act the way they do. This undermines the entire novel, leaving you feeling cheated – the wonderful potential implied by the title and premise have been wasted. Had the dynamic between Julia and Valentina been fully realised, the plot unfolded from the very beginning instead of crammed into the end, and the dark aspects of the plot fully drawn, it could have worked. The truly interesting plot elements are rushed through in the last couple of (very short) chapters, while the majority of the book is filled with endless descriptions, almost none of which are relevant to the plot.

The one redeeming feature of the entire novel is that it is written by Niffenegger. That really is the extent of the praise that can be offered. Niffenegger has a way with descriptive prose which is truly unique and a pleasure to read. That is not nearly enough, however, to compensate for the absurdity of the plot developments and flaws in characterisation. Overall, the book reads like a first draft; raw, undeveloped, full of mistakes and plot holes. Had this book been honed, and truly explored to the extent of its potential, with the first half of it cut down to the barest minimum and the last quarter expanded extensively, it might have been good.

Never has a published book more thoroughly demonstrated the benefit of drafting and redrafting a novel, no matter how painful the process might be; never has a book been more in need of a good editor.