‘It’s not about the money, money, money, we don’t need your money, money, money

Just want to make the world dance, forget about the price tag’

I first heard this song as played through the built-in music system of a high-street chain store. The irony was not lost on me, in fact, within the context of the busy store it seemed like an encouragement for customers to forget the ‘price-tag’ of their items and enter into a reckless consumerist spree, buying any item that might aid them in the dance of life.

The song has, in it’s way, a noble, if not slightly pre-digested, sentiment. That music should be for the lubrication of one’s feet (or minds) rather than their pocket is an idea that has been held to the chests of musicians for a while. But when did this idea that ‘popular’ music (and by definition, salable) should have a kind of artistic integrity to it take hold? It can’t have been with the birth of rock’n’roll. Sam Phillips knew the value of finding a clean cut ‘white boy’ to sing the blues, and doubtless Elvis had no qualms about singing music written by other artists and writing teams, and leaving the inspirers (or perhaps more correctly, inventors) of the music penniless. Motown records churned out records weekly in pursuit of top ten hits. So when did musicians become art-ists with desire for integrity and investment in their songs?

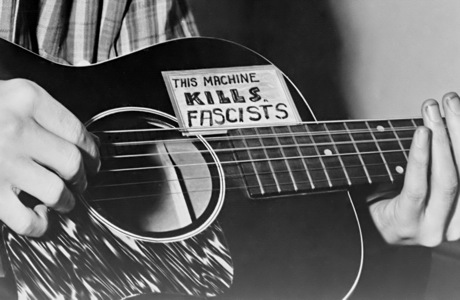

The root, it seems to me, is in folk music. In fact, I have a written record of perhaps the first moment that a musician decided to forgo payment in return for their own integrity. Of course I cannot be sure it is the very first, but it could be the most influential. In Woody Guthrie’s autobiography ‘Bound for Glory’, he writes of finding himself playing to a team of advertising executives in a New York skyscraper. ’65 storeys back to the world.’ he says, ‘Quite a little elevator ride down to where the human race was being run’. After having his song described as ‘Extremely colourful’ though not necessarily ‘suited to our customers’, a short discussion of his image is had and it is thought that a Pierrot costume might best endear the clientele to his style of music. Imagine, if you will, the influence this moment could have had on contemporary culture. The whole fate of a counter-cultural movement yet-to-come held in the bauble of a Pierrot costume. Mr. Guthrie declines the offer of working for the advertising company, takes the long elevator ride down to integrity and sings to the people on the streets below, for free, and inadvertently defines what we think it is to be a ‘real musician’.

The Bob Dylan – Woody Guthrie link has no need for being retold here, neither does the story of ‘going electric’. However, one aspect of the flick-switching might not be forgot. The folkies (fans of folk) said of Dylan at the time that he was ‘selling out’. Putting together an electric band was seen as trying to integrate yourself into the mainstream and the folk-fans saw this as a betrayal of everything sacred in their noble tradition. In their eyes, he might as well have donned the Pierrot costume right then and there. But by today’s standards this is a tame concession to have made, if indeed it was made at all, to the popular consensus. Artists change style from track-to-track in the hope that one will stick. Coldplay’s latest releases seem calculated for use in night clubs, and this is probably put down to musical ‘evolution’, y’know because they’re artists exploring new areas of music. That happen to be very popular at the moment. Perhaps they just want to make the world dance.. It should be noted as well that punk-integrity hero Joe Strummer did once have long hair, the nickname ‘Woody’ and a blues-rock style band called the 101’ers before ‘punk’ became a plausible marketing strategy, admittedly being marketed by fairly implausible people (at your own risk, have a research around the Clash’s first manager Bernie Rhodes).

So we must ask ourselves are these apotheoses of integrity merely illusory, or just savvy? Is there any value to art never appreciated? Are the trappings of trends a worthy price to pay for successfully engaging with an audience? Maybe we should ask Robbie ‘Rudebox’ Williams ‘was it worth it’? For myself, I retain the right to be suspicious of anyone who will, for no other reason than the right money, lend their voice to anyone else, in particular those who make their name by that voice. Jessie J, made famous by ‘Price Tag’, sponsors Mastercard. Though I held no real hope for her to be the voice of a generation of disaffected blah blah blah, the disparate nature between her song and her actions are verging on the hilarious. Also it irked me that no one has called her out on it.

It would be very grown up and considered of me, perhaps, at this point to make a case for the other side. Something along the lines of ‘But it’s just a song, it doesn’t matter does it? Everyone has to make a living. You’re just jealous. Mastercard isn’t evil just because it’s a big corporation’ but I shan’t. The independence of an artist’s voice from any kind of business interest is a matter of respect; to the tradition of songwriting, to the artist and to the audience. If you want to be a Pierrot in a pantomime then be one, but don’t don the costume for a paycheck.

Nice one, good to see the latest trend of artistic integrity isn’t as elusive to everyone as I first thought. And how incredibly ironic that such an idea has become a craze in itself.