David Cameron has got a problem. It’s a problem nearly every post-war prime minister has had, and not many of them have found a satisfactory way of dealing with. What do you do when your party becomes unpopular in Government and voters start to drift towards alternatives?

Most people knew that by this point in Parliament the Government would be unpopular. Cutting public spending at rates not seen for decades and restricting benefits for those most in need was never going to lead to cabinet members being paraded through the streets on the shoulders of grateful electors. But not many people predicted the way that voters would go, and the effect this seems to be having on political debate in this country.

Governments are always unpopular half way through their term, and they very rarely gain seats at by-elections. What usually unites them is the ability to brush it off and say “None of this matters, we’ll still win the next general election.” Blair successfully did it for seven years, and Gordon Brown continued it for the next two, just with slightly less eventual success.

The problem that David Cameron and the Tories have is that they can’t just brush off their unpopularity. They can’t say “We’ll win again next time” because they didn’t win last time. They haven’t won an overall majority for a generation, something many Tory MP and lots more of the wider membership continually remind Cameron of.

Another thing that makes it harder for Cameron to shrug off his unpopularity is, unlike the last Labour Government, there is a refuge for those traditional right-wing Tory voters. Some former Labour voters flirted with the Lib Dems, but they tended to be those who were only attracted to the New Labour project. When the hard-core of the Labour membership fell out of love with Blair over Iraq, top-up fees, foundation hospitals or being too close to business, they largely drifted away from party politics. Cameron’s deserters are drifting to UKIP, and it’s changing the political debate of the country.

UKIP might have come a long way since it was founded in the early nineties, and the leadership of the party has undoubtedly worked hard to promote it as much more than a single issue party available for protest votes at unimportant elections. Despite all this work though, UKIP still mainly focuses on withdrawal from the EU and the subsequent control the UK would regain of domestic policy, especially immigration.

It’s no secret that the Tories are split on the issue of Europe. In fact every political party is. I know Labour MPs who despise the way the EU has imbedded capitalism and halted the evolution of European Socialism. I know Tory MPs who hate the EU because it has restricted capitalism through its forced implementation of European Socialism. In fact about the only party that stands united on Europe is UKIP. And the public like it when political parties are united.

So David Cameron has decided to tackle the issue head-on. He’s not going to hope that the arguments on immigration and Europe will disappear and that the Tory faithful will forgive him everything else by 2015. He’s made two speeches this year in a bid to meet the UKIP threat head-on. On both occasions they have been spectacular failures.

The first speech in Europe came in January, with the Prime Minister promising a renegotiation of the UK’s relationship with the EU *if* the Conservatives win a majority at the next general election followed by a referendum with an in/out option *if* those renegotiations are successful. Critics immediately spotted that Cameron would be going into the process wanting to stay in the EU anyway, hardly the best starting point for talks and without a clear idea of what powers he wanted to bring back from Brussels. UKIP immediately came out and said it was all too little too late and they would withdraw immediately, no questions asked.

Then last week there was the speech on immigration, and the way that immigrants were able to access benefits in the UK immediately upon arrival. As with many politicians discussing issues of immigration (not all on the right either) the speech strayed dangerously close to what some would call ‘incitement’ and others may label even more strongly. The thrust of the speech was to severely restrict access to benefits for those who came to the UK as immigrants, with the cost on the NHS the main focus. Cameron said in the morning that the cost was tens of millions per year, only to be trumped by Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt not two hours later saying the cost was hundreds of millions. The truth is probably that nobody knows.

The right-wing press seemed to like the speech, the comments section on the Daily Mail website was approving. But then out come UKIP to say not only would they stop immigration completely, but they would also severely restrict benefits to those already in the UK. All benefits, that is, except those being paid to UKIPs core vote (state pension, winter fuel allowance, free TV licence, bus pass). Once again Cameron’s rhetoric is lost in the tub-thumping of the mainstream extreme right.

The beauty of all this for UKIP is of course they have absolutely no chance of ever being asked to put any of it into action. We all thought that about the Lib Dems before the last election, presuming that’s why they were offering to abolish tuition fees. UKIP starts from an even lower base, and with the added advantage of everything they say being recorded because the main governing party is terrified of them and they continue to do well in the opinion polls.

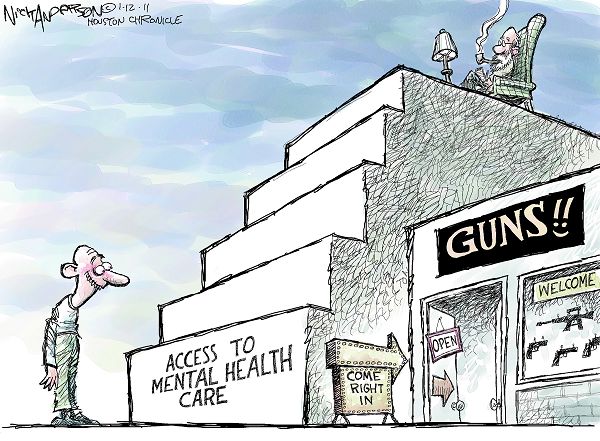

Not all Cameron’s efforts have been in vain though. He has managed to somehow draw Labour and the Lib Dems into this Dutch auction on benefits and treatment of migrants, having previously done so with the EU issue. We now face the prospect that all three parties will spend the next two years telling us how they are going to ensure that the most vulnerable in society deserve to be treated badly. The next leadership debates will feature Ed, Nick and Dave scrambling to outdo each other in how tough they will make it for sick people to get treatment and for the working and non-working poor to survive.

It may well be the only thing we remember about David Cameron in 20 years’ time.